FRANCIS HUYSHE

Vindication

of the

Early Parisian Greek Press

A Correspondence extracted from:

The British Magazine (London) Vol III. 1833:

pp. 283ff., 427ff., 548ff., 658ff.

and

The British Magazine (London) Vol. IV. 1833:

pp. 29ff., 161ff., 276ff., 411ff., 530ff., 632ff., 757ff.

An examination of the sources and methods of Robert Stephens in

his production of the Textus Receptus Editio Regia

In which reference is made to,

and to which accordingly is prefaced:

A

SPECIMEN

OF AN

INTENDED PUBLICATION

(1827)

by the same author

A

SPECIMEN

OF AN

INTENDED PUBLICATION

WHICH WAS TO HAVE BEEN ENTITLED

A VINDICATION OF THEM THAT HAVE THE RULE OVER US, FOR

THEIR NOT HAVING CUT OUT THE DISPUTED PASSAGE,

I JOHN V. 7, 8. FROM THE AUTHORISED VERSION.

BEING

AN EXAMINATION

OF THE

FIRST SIX PAGES OF PROFESSOR PORSON’S FOURTH LETTER TO TRAVIS,

“OF THE MSS. USED BY R. STEPHENS.”

BY FRANCIS HUYSHE.

_______

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR C. J. RIVINGTON,

ST. PAUL’S CHURCH-YARD,

AND WATERLOO-PLACE, PALL-MALL

______

1827

{Editor’s Note: the following work is an analysis and rejection of the criticism attacking Stephanus’ claims regarding the manuscripts he used to produce the Editio Regia 1550. In this work, the “Specimen,” the focus is on Stephanus’ text at I John 5. 7 (the so called “Johannine Comma”). Stephanus based his text on manuscripts obtained from the Royal Library of France, which were later confiscated by the Roman Catholic authorities because he was suspected of “heresy.” The disappearance of these manuscripts was later used by critics to accuse Stephanus “by error or fraud” of having forged his Greek Testament. This charge is thoroughly refuted here by Huyshe. One example of the charges leveled at Stephanus is that when he listed in his margin “all” the manuscripts which he had showing a different reading from those he used for the text itself, it was imagined he meant “all” the manuscripts in toto had the reading that was different from that found in the text, not merely “all” the opposing or variant manuscripts, which could only mean Stephanus invented the reading in the text himself! This ludicrous idea contributed to the belief that Stephanus based his text mainly on the 5th edition of Erasmus and the Complutensian printed text. That is amazingly still the accepted “scholarly” consensus today. Which is why it is important to publish more widely the amazing and thorough refutation of such critics by Huyshe.

Additionally it should be noted that Francis Huyshe acknowledges a fault in the Specimen as here reproduced, which he admits on p. 634 of the Vindication (p. 90f. Infra):

“I must not quit [the manuscript] ιε without making due acknowledgment of my faults, and of my obligation to this note (ii. 782, note 275) for its having made me sensible of them. An abominable blunder pervades the Specimen, which blindly follows the Docti et Prudentes, {Latin: “Learned and Wise”} in representing the whole of the fifteen marked MSS. to have been taken to furnish opposing readings to the first volume of the folio. I trust that in future I shall have enough of that σωφρων απιστια, {Greek: “sensible unbelief”} which Mr. Porson so justly recommends, p. 163, never again to trust to their representations. Wherever the marked MSS. of Stephanus’s margin are mentioned in the specimen, the reader will now see that instead of xv. which the pamphlet gives, it ought to have been “the first thirteen;” and he is requested to correct it accordingly.}

ADVERTISEMENT

_______

THIS publication is occasioned by an advertisement in the newspapers, which announced, that we might expect a Defense of Mr. Porson against Bishop Burgess, by Crito Cantabrigiensis. {Crito Cantabrigiensis is the pseudonym of Thomas Turton, Regius Professor of Divinity, St. Catherine’s Cambridge, 1827-1842.} My veneration of the abilities and acquirements of Mr. Porson is unbounded: “forty thousand” sons “could not, with all their quantity of love, make up my sum.” {From Hamlet V. i. 254-256.} I can speak of him only, as Dr. Parr does, “Richard Porson, του πανυ θαυμαστου {Greek: “the most amazing”}.” But if you talk of “an invincible love of truth, an inflexible probity,” you sap the foundation of my idolatry; and he stands within the prospect of comparison with his blundering correspondent. The reader has before him a specimen of my reasons for saying, that if the world was taken captive by him at his will; his own understanding did not bow to that will. And I have to make my grateful acknowledgments to Crito Cantabrigiensis, for his irresistible excitement to this part of my proposed work; as the whole probably would otherwise have been deferred till the night cometh, when no man can work. Should he think this not sufficient to establish my opinion; he shall have more of it; and he shall have it too, upon the Complutensian edition, and the Ravian MS.; upon Erasmus’s third edition, and the MS. that was sent to him from England; upon the kindred reading discovered in the Montfortian MS.; upon the West African recension; and above all, upon the internal testimony of the passage—till he cries “hold, enough.” But I am not without my hopes, that the favour, conferred upon me by Crito Cantabrigiensis, may be repaid by my saving him the expense of paper and print: and I feel confident of being allowed to doze out whatever may yet remain of the evening of life, without interruption from any other quarter. I have not to learn the truth of what the Trojan lady said,

λογος γαρ εκ τ᾽αδοξουντων ιων

Κἀκ δοκουντων αυτος ου ταυτον σθενει

{Greek: “….. the word that goes forth from those undeserving of credit, and even from those worthy of credit, does not validate the same.”}

And I am satisfied with thus publicly entering my protest on these heads; and with having furnished a clue, by which any one, who will use a little industry, may extricate himself from that labyrinth of fraud, which nearly two centuries have now been constructing round Stephanus and the received text.

July, 1827.

EXAMINATION,

&c.

____________

MR. PORSON in his fourth Letter attacks the testimony of Stephanus to the disputed passage of St. John; and he prefixes the motto,

“What, will the line stretch out to the crack of doom?”

{From Macbeth 4. 1. 122.} I reply, not by my pulling. I claim nothing here but the authority of one of Stephanus’s unmarked MSS.

The Letter begins, p. 54.

“How formidable an host you are now leading to battle! Sixteen MSS. of Robert Stephens, all containing the heavenly witnesses! We may however spare our alarms; for all these MSS, upon a nearer inspection will prove Phantoms bodiless and vain, empty visions of the brain.”

I cannot be satisfied with calling them “empty visions.” If Mr. Porson had not taught me, p. 26, to “acquiesce in the milder accusation of shameful and enormous ignorance;” I should have declared that the man who could possibly cite any of those sixteen copies, must have been bribed to betray the cause, and to ruin the authority of Stephanus’s editions. After Mr. Porson’s having demonstrated, as he certainly has done, that “the semicircle is wrong placed” in the text of the folio (i.e. that it ought to have comprehended not merely εν τῳ ουρανῳ {Greek: “in heaven”} as not appearing in the seven MSS. of the margin, but the whole of what [Specimen 2] is now most commonly marked for excision)*

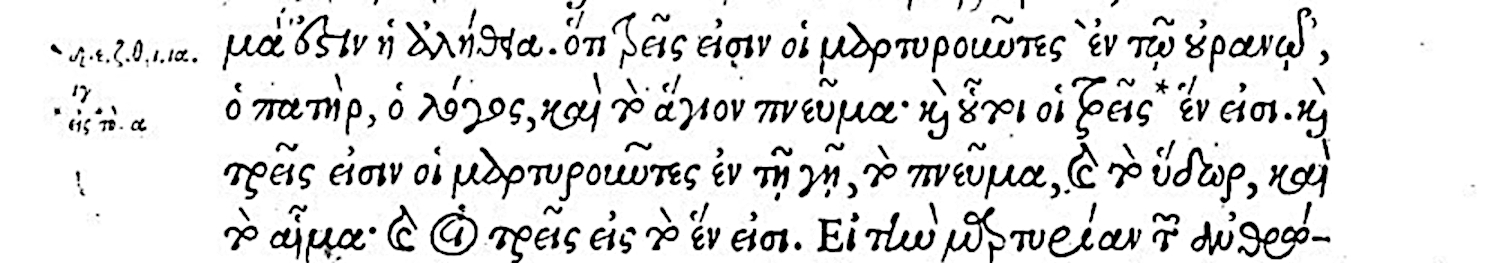

*{Editor’s Note: The reference here is to the text of Stephanus 1550 at I John 5. 7. This reads in translation: “There are three that bear record in heaven: the Father, the Word and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one.” Stephanus’ manuscripts which he used for his reading read “in heaven” but to the left of the Greek words “in heaven” he placed a diagonally-angled mark, and to the right of them a “semicircle” to show that the seven manuscripts quoted in the margin at this place, did not include the words “in heaven.” Thus:

From this we see that his main set of manuscripts used for the text itself included the words “in heaven” but the manuscripts labeled in the margin δ, ε, ζ, θ, ι, ια, and γ, did not include those words. Because these variant manuscripts (omitting the words “in heaven”) are no where to be found nowadays (having been confiscated or destroyed by the Roman Catholic authorities in the early days of the Reformation, along with the manuscripts used for the text itself), it is concluded wrongly by the critics refuted here by Huyshe that the whole phrase “there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one” etc. is what Stephanus intended to mark as not appearing in his manuscripts.}

he says, p. 82, “when we add to this that Wetstein found at Paris five manuscripts, which agree with five of Stephens’s manuscripts in other places, but here contradicted his margin, none will hesitate to pronounce, that Stephens’s copies followed the herd, and omitted the seventh verse, except only those, who by a diligent perusal of Tertullian have adopted his maxim of reasoning, and measure the merits of their assent by the absurdity of the proposition to be believed.” I ask, which of “Stephens’s copies followed the herd?” People may perhaps be deterred from putting this question, for fear of sharing the fate of Tertullianus; for whom by the bye, I think that I could have said enough to have shamed Mr. Porson. If the question had ever been asked; what could Mr. P. have stated more than those out of the fifteen MSS. of the margin, which happened to have this chapter? But let it be observed, that we are establishing the received text, and not opposing it—that we are not contending for the reading of the MSS. of Stephanus’s margin, which differ from the text; but for that of the text of his first and his second edition, which he very properly followed in the third.

P. 54, “I shall lay down the real state of the case, and then confute your cavils. Mr. Gibbon gives his readers the option between fraud and error.”

Yes; Mr. Gibbon does give his readers the option, and so leaves me no option for my opinion with respect to himself. Ch. xxxvii, note 119, “The three witnesses have been established in our Greek Testaments by …… the typographical fraud or error of Robert Stephens in the placing a crotchet.” I have no objection whatsoever to one gentleman’s demonstrating that the “crotchet” was placed falsely by fraud; and another demonstrating that it was misplaced by error. But if this identical Mr. Gibbon can show cause for intimating that it was done by fraud, where was the blunder? if he can show, that it must have been by mistake, how am I to characterize the [Specimen 3] insinuation of fraud, that is thrown out in the same breath? Mr. Gibbon then is so kind as to give his readers the option, where he had no right to speak, if he could not decide. But this complaisance is amply compensated by his peremptory decision, that the wrong placing of his crotchet was typographical. I am not aware that he or any of the learned gentlemen, who refuse their readers the option, (as Mr. Porson does, particularly at p. 132) have assigned any ground for suspecting that the compositor did not place the lunula as it stood in the MS. And if I depended on that silence alone, I think I may venture to defy any man to show a reason for the assumption of the error being typographical, but that Stephanus is not to be got rid of without it.

P.54. “I am always unwilling to attribute to fraud what I can with any reasonable pretence attribute to error. But if any person be more suspicious than I am, he needs not be frightened from his opinion by your declamation.”

Certainly not by Mr. Travis’s declamation: but he is fool hardy indeed, if he be not frightened by Mr. Porson’s silence. Let us see how this gentleman, that is to be “more suspicious than” Mr. Porson, is to argue.

P. 54. bott. “For when he considers how Erasmus was worried for speaking his mind too freely, —”

We may find out how this was from Mr. Porson at p. 354. “From these examples, I hope, it will appear, how falsely that infamous villain Erasmus asserted that Christ is seldom called God in the N.T.” Erasmus had asserted in his first edition, on John i. I., “haud scio an usquam legatur dei cognomen aperte tributum Christo, in apostolorum aut evangelistarum literis praeterquam in duobus aut tribus locis.” {Latin: “I do not know whether the cognomen of ‘God’ is ever attached plainly to Christ in the writings of the apostles and evangelists except in two or three places.”} For this he was “worried:” and I trust that there never will be a time, when a man shall presume upon the ignorance of others, to make such an assertion, without being worried. Erasmus then makes what excuse [Specimen 4] he can, in his second edition, and in his answer to Stunica; and abandons his assertion. Observe now the suspicious gentleman’s mode of reasoning. Erasmus was worried for speaking his mind too freely in a note on the indisputable text, John i. 1.; therefore Stephanus, in stating what those MSS. said, that opposed the reading of his editions on 1 John v. 7, 8, was wilfully to place his marks wrong. Was Erasmus worried for giving nothing but what he found in his MSS. on our passage? If you think so, you cheat yourself by adding to the Professor’s words. Mr. Porson dared not say so. He tells you himself plainly enough how far Erasmus was from being worried for the omission. “I ask, therefore,” says he, p. 45, “what could induce Stunica, who is at other times scarcely less virulent against Erasmus than Mr. Travis himself is, what could induce him to be so mild and tame in this particular instance?” But this is not all: the Pope himself actually patronized Erasmus’s second edition, which exactly followed the first on this passage. (Butler, Hor. Bib. xi. p. 151. ed. 4. Butler’s Life of Erasmus, p. 172. Maces, note p. 929. and 934.)

P. 55 “—and with what jealousy R. Stephens was watched by the Paris divines—”

Mr. P. here omits to inform you to what point that jealousy went; as he did before, for what Erasmus was worried. We may turn then to Simon, Versions x. p. 134, b. “Je diray seulement en general, que R. Estienne y avoit inseré a dessein quelques expressions ambigües qui favorisent les sentimens des Protestans:” {French: “I would say in general that R. Stephens had inserted deliberately certain ambiguous expressions which favored the views of the Protestants:”} and Comment. xxxix. p. 566. a. “Mais il s’attira cette censure, ayant affecté de certaines notes qui sembloient favoriser les nouveautez des Protestans: {French: “But he brought upon himself this censure, having added certain notes which appear to favor the novelties of the Protestants:”}:” and when Henri II. gave him up to their will, he wrote, Nov. 25, 1548, “—ne voulant aucunement tolerer ne permettre chose qui soit pour detourner nos sujets de la droite voye Catholique—” {French: “not wishing at all to allow permitting anything which would lead to turning our subjects from the right Catholic way”.} And what effect this jealousy had upon Stephanus, may be seen from his editions of the Vulgate, where the lunula is constantly in its right place.

[Specimen 5] P. 55. “—— it cannot appear incredible that Stephens might make this seeming mistake on purpose;—”

“Seeming mistake.” It is not Mr. Porson’s mode to deal in seemings; and least of all on this point. Let the suspecter make it out to be a “seeming mistake” only; and the objections to the notation in Stephanus’s folio, become the “phantoms bodiless and vain.” Mr. Porson will then justify that enormous absurdity which Mr. Travis could believe, that there could have been found seven MSS. that agree in mangling the text, (I believe this is Mr. T.’s own expression,) by leaving out εν τῳ ουρανῳ {Greek: “in heaven”}, “But,” as Mr. Porson justly says, p. 69, “that seven Greek MSS. collected by the same person from different places; seven MSS. of different ages and merits, should all consent in a reading, that no critic or editor has been able, during the space of two centuries and a half, to find in any other MS. whatever, Greek or Latin, is such an excess of improbability, as the very men who maintain here, would be foremost to ridicule in any other dispute.” And Griesbach [7], 691 Lond. 1810, “Vix enim comminisci potuissent quidquam tam incredibile, quam est illa de codicibus Stephanicis fabula.” {Latin: “For they would hardly be able to recall a thing so unbelievable as that fable about Stephanus’s book-form manuscripts.”} And I am to be told by Mr. Porson, that “it cannot appear incredible,” that Stephanus might have made this “fabula”—this “excess of improbability” on purpose.

P. 55. “——so far, like Zacagni, (see Letter II. p. 33.) honest in his fraud, that he furnishes every inquisitive reader with the means of detection.”

For an instance of fraud in this case, Mr. P. is obliged, we see, again to have recourse to Zacagni. We shall see how far even Zacagni can serve him, if we are to go together over the passage here referred to.

After all, I say to those who are willing to attribute the wrong position of the lunula to fraud; and are not “frightened from” asserting that Stephanus made “this seeming mistake on [Specimen 6] purpose”—Can you not devise a method, by which he might have done this much more easily, to much better “purpose,” and by which it could never have been shewn to be even a “seeming mistake?” What think you of leaving a blank in his margin? His simple silence, as I conceive, would have supported this text, which he gave from his former editions, with all the marked MSS. that had the epistle. I see an obvious motive, then, for such a mistake as that being made on purpose. But by what means, I should like to know, was Stephanus ever to have had a suspicion of the possibility, that such exquisite management, and such intense stupidity, could meet together; so that it could be made the great question of criticism, whether or not he established the three heavenly witnesses in our Greek Testaments, by “the placing a crotchet?” By what means was he to foresee that there should be a Gibbon to be attacked by a Travis, and to be defended by a Porson and a Marsh? I can conceive nothing more futile, more absurd, than the introducing of the folio edition into this question, with the opposing readings of the fifteen MSS. of the margin. But I have thought it right to let the reader see what sort of justice is to be expected at the hands of Mr. Porson; when he can give his consent to have Stephanus condemned upon such grounds: “si poteris recte, si non, quocunquemodo” {Latin: “if you can, properly, if not, by any means whatsoever”}—

P. 55. “But as I am content with the other supposition, I say,—”

Mr. Porson is content, for himself, to attribute to error, what he cannot with any reasonable pretence attribute to fraud: so he says,

P. 55. “1. That Henry Stephens and not Robert collated the MSS.”

Mr. Porson has admirably adapted this to the phantoms of that brain, which could never dream of any thing but the collation of the marked MSS. for the margin of the folio. Let Mr. Porson, or any one of the learned and acute men who have [Specimen 7] made such an assertion as this, have changed places with the poor Archdeacon; and he would have enquired what collation was meant, and which set of MSS.*

{[Note:] * The Preface says “Superioribus diebus ——N. T.—— cum vetustissimis sedecim scriptis exemplaribus——collatum, minore forma, minutioribusque Regiis characteribus tibi excudimus. Idem nunc iterum et tertio cum iisdem collatum, majoribus vero etiam Regiis typis excusum tibi offerimus”—— {Latin: “At an earlier period ——the New Testament——collated——with sixteen very ancient hand-written exemplars, we printed for you in a smaller format, and with smaller Royal characters. This once again a third time also collated with the same exemplars, we provided to you in printed form in a larger Royal typeface.”}

It then proceeds to give an account of the margin, and of various readings preserved in it, where the new text of the folio differs from fifteen of the MSS. that had been obtained from all sources, and a printed edition, all of which are denoted by the Greek numerals.}

Robert tells us in the preface to the folio, that there were three collations of the XVI MSS. with which he began his critical career; and to whatever text they were referred, it was different from that with which the XV of the margin were collated; for that was the new text of that edition.

When Mr. P, is pleased to assert his negative, “and not Robert,” does he mean that he could give the slightest ground for suspicion that Robert never took part at any time, in any one of the collations? Why might not he, or any one of the ten learned foreigners, of whom Henry gives an account in his epistle prefixed to his Aulus Gellius, (Almeloveen, p. 31. Maittaire, p. 18.) or Vatable, in giving the readings of his own MS. ιγ, have borne a share in the collations? Can you show any one, besides Robert, who was concerned in the collation for the first edition? Certainly not Henry, for we shall see that he lays claim to the honour of collating only for the folio, and the duodecimo, which had just preceded it. Can you show any ground for asserting that none of the MSS., of any set, were in foreign countries—Spain, Germany, England, Italy; so that neither Robert nor Henry ever saw them themselves; but must have been furnished with the various readings by others?) Semler seems not to have thought any thing of the kind improbable. He says, in note 281 on Wetsten’s Proleg. p. 373, “Ceterum non est dubitandum, codices regios et qui in propinquo erant, non sine patris arbitrio et adjumento a filio collatos fuisse.” {Latin: “But it is not to be doubted that the Royal book-form manuscripts and which were at hand, were collated by the son, with the authorization and help of the father.”}

[Specimen 8] P. 55. “2. That the collation was probably inaccurate and imperfect.”

No doubt this was the case with every one of the collations of every set. I never heard of any collation that was not so. The second and the third collation of the first set, evidently admits as much.

P. 55, “3. That it certainly was not published entire.”

Most certainly. As Semler says (ubi supra) “Robertus ipse maxime elegit ea que voluit typis exhibere, caeteris interea sepositis, quibus postea, cum Henricus communicaret, usus est Beza.” {Latin: “Robert himself made the principal selection of those [sc. exemplars] which he wished to bring out in print. Others became available in the intervening period, which latterly, when Henry shared them, Beza used.”} Robert undertook only to give V. L. {different readings} from the Complutensian edition, and from XV MSS. He does not profess to give any thing from the rest of his authorities, whether printed or manuscript. We therefore know nothing of these parts of the collations of his MSS. but from one single note, I believe, of his own; and from some casual V. L. {different readings} “quibus postea, cum Henricus communicaret, usus est Beza,” {Latin: “which latterly, when Henry shared them, Beza used”} in his commentary.

P. 55. “4. That Stephens’s margin is full of mistakes in the numbers and readings of the MSS. 5. That the marks in the text are often misplaced or omitted. 6. That some of the very MSS, used by Stephens having been again collated, are found to agree in this critical passage with all the rest that have been hitherto examined. And 7. That therefore the semicircle, which now comes after the words εν τωι ουρανωι {Greek: “in heaven”} in the seventh verse, ought to be placed after the words εν τηι γηι {Greek: “in earth”} in the eighth.”

To this I reply, and what then? Does this show that the acknowledged error in this place was typographical? And does all this tend in the slightest degree to show what Mr. P. undertakes to establish, viz. that Stephanus’s error affects our Greek testaments? As for the folio and its margin, I only ask you to leave me the first words of the preface, and [Specimen 9] those readings, which demonstrate the truth of what appears there, viz. that he had another set, out of which he formed his first edition (cum vetustissimis sedecim scriptis exemplaribus {Latin: “with sixteen very ancient hand-written exemplars”}) besides that of the XV which he marks with the Greek numerals; and you may (as far as this question is concerned) sacrifice the rest to the vanity of modern editors. The notion that the Epistle of St. John was contained in any other of the XV marked MSS. than those which are quoted in the margin, I consider the most empty vision of the most addled brain. And place the semicircle wheresoever you like, it still denotes a reading, that is more or less at variance with “our Greek Testaments.” When therefore the acute historian was talking about typographical fraud or error in placing a crotchet; he was only placing a crotchet in those addled brains. When Mr. Porson, pref. p.ii. with such inimitable skill, contented himself with the delicate insinuation, “that R. Stephens, in his famous edition of 1550, inserted the verse,” &c., he showed that he felt his total inability to “gainsay or resist” the two despised editions of 1546 and 1549, which had given the passage in the new form. And what shall I say of Mr. Butler; when, Append. Hor. Bibl. ix. (p. 274) he tells us with unblushing front, “With respect to Robert Stephens’s manuscripts;—To explain this part of the case, to persons unacquainted with Stephens’s celebrated edition of the Greek Testament, which gives rise to the present question, and which was the edition published by him in 1550—it is necessary to observe that the text of it is a re-impression of the fifth of Erasmus, with a few alterations.” Mr. Butler might safely depend upon his readers being “persons unacquainted with Stephens’s celebrated edition.” But what in reality had that “famous edition of 1550” to do with the point at issue, more than the fourth of 1551, or any one of the Elzivirs? Where is there a single Greek Testament exhibiting that reading which would be made by the “semicircle wrong placed.” (p. 82)? Where is the critic that has ever contended for it? Of all those, who have been ruining the cause by their [Specimen 10] defense, I know not one, whose folly has been sufficient for him to intimate, that such a reading could possibly have been given by the apostle. Beza immediately declared respecting εν τῳ ουρανῳ which would be thus rejected, “omnino videtur retinendum, ut tribus in terra testibus ista ex adverso respondeant.” {Latin: “By all means it seems it should be retained, so that there should be a correspondence between the three witnesses on earth and these contrariwise.”} And all the world has acquiesced in his judgment. When therefore Mr. P. proves, that the lunula “ought to be placed after” εν τῃ γῃ {Greek: “on earth”} what is it that he shows, but that the fifteen marked MSS. were all either without the epistle, or without the passage; and therefore that none of them opposed that reading of it, which Stephanus had given in his former editions? And if common sense and common honesty had been brought together to the question; it could not have remained for me to tell the world, that the received text in this passage was established in the first and the second edition of Stephan{us}: [I mention the second, because it corrects a typographical error of the first, not noticed in the table of errata,] nor when the fifteen marked MSS. are proved to have been all without it, that it must have been established there, from another part of the collation, which as Mr. P. so justly observes (3) “certainly was not published entire.”

P. 55. “You, Sir, answer in the first place, that H. Stephens was not the sole collator of the MSS. ‘because there is no pretence for the assertion, and because reason, propriety, and probability, are all uniformly against it’ p. 297. Now this is so fully proved in Wetstein’s Prolegomena, p. 143, 144, that I should even be tempted to hope that if you had read them before you wrote your letters, you would have spared yourself a considerable quantity of disgrace and repentance (p. 56.).”

All this “quantity of disgrace and repentance,” that Mr. Travis was to have been saved by reading Wetsten, I must incur, after having attended to all that both he and Mr P. have urged. Without thinking for a moment of Henry’s character, “In suis certè scriptis frequentius suae laudi studet;” {Latin: “Certainly in his writings he frequently affects to sing his own praises.”} (Maittaire 485, [Specimen 11] quoted by Travis 3rd ed. 254.) I cannot see one of the quotations from him, that says any thing like “and not Robert.” So far from proof that no other person was concerned in any part of the work of collation, I am unable to discern an intimation that any one of the collations of any one set of the MSS. was performed by Henry alone; or that Henry had any concern in the collation of the XVI, for the first edition, or of any one of the printed authorities. And I must add to the quantity of my disgrace and repentance, by saying that the notion of the whole having been performed by him alone, appears to me an absurdity, which nothing but gross misrepresentation of facts, could have made pass in the world.

P. 56. “I shall repeat Wetstein’s last quotation. Pater meus—cum N. T. Grecum cum multis vetustis exemplaribus OPERA MEA COLLATUM, primo quidem minutioribus typis—mox autem grandibus characteribus, &c.” {Latin: “My father—when the Greek New Testament HAD BEEN COLLATED THROUGH MY ENDEAVORS with many very ancient exemplars—first in smaller typeface,—but soon in larger characters ….”}

Though this may be, as Wetsten says, “luce meridana clarius,” {Latin: “clearer than the mid-day sun”} for the confutation of his opponent’s absurd theory; what does it effect for substantiating his own? Henry says, “mea opera collatum,” {Latin: “had been collated through my endeavors”} I see nothing like “mea solius opera.” {Latin: “only my endeavors.”} Henry says, “cum multis vetustis exemplaribus,” {Latin: “with many very ancient exemplars”} not, as some gentlemen are pleased to assert, “cum XV tantum.” {Latin: “with 15 only”}. Henry says, “primo quidem minutioribus typis—mox autem grandibus—,” {Latin: “first in smaller typeface,—but soon in larger”} not a hint about the original edition of 1546—not bis quidem minutioribus—deinde grandibus {Latin: “twice in smaller typeface, but soon in larger”}. I can see nothing, but what might have been said by a man without a spark of Henry’s vanity, supposing him to have been at the head of the business, (primo quidem {Latin: “first”}) in recollating the XVI original MSS. for the second 12mo. edition of 1549, and soon afterwards (mox autem {Latin: “but soon”}) in the different collations for the folio of 1550; in the first place, of all the MSS. for forming the text, and then of the XV with that text for the margin. And I hesitate not to say, that if Mr. Porson had seen any thing of the kind, he would have distinctly pointed it out; and not contented himself with merely repeating [Specimen 12] Wetsten’s gratuitous assertion, “sole collator :” and “disguising the fact in a general expression” (note in next p.) “of the MSS.” A few words to that purpose, would have more effect upon my mind, than any intimation of the quantity of disgrace and repentance that is to befal me, if I venture to question the decision of the critics, that no person but Henry, collated any one of the MSS. that Robert used for any one of his editions.

The deduction from these words of Henry, appears very similar to that which the learned are pleased to make from what he says in his Concordance, respecting his father’s subdivision of the text in his last edition. Henry says, “At contra eorum damnatricem instituti patris mei opinionem, inventum illud simul in lucem, simul in omnium gratiam venit.” {Latin: “And in spite of their condemnatory accusations they took up my father’s idea, and that invention was introduced into the world, to the grateful acknowledgement of all.”} That division into verses, which we now follow, was the invention of Robert Etienne, as Henry here tells us. But what say our critics? They call “Robert Stephens the first inventor :” (Michaelis, Vol. II. ch. xii. sect. xi. p. 527.) “for the first time the numerals were marked in the margin of his small edition of 1551.” (Dr. J. Pye Smith, Eclectic Review, April, 1809, p. 330.) It “is remarkable for being the first edition of the New Testament divided into verses.” (Horne’s Introduction, Part I. ch. iii. sect. ii, vol. ii. p. 186, 3rd ed.) But Brett, Dissert. on the Ancient Versions, in Watson’s Tracts, p. 49, says, “Vatablus, a Frenchman and an eminent Hebrician, about an hundred years after Rabbi Nathan, taking his pattern from him, published a Latin Bible with chapters and verses numbered with figures.” Bengel Apparat. § xxxvi. p. 71. ed. 1763. “Atque antea Jacobus Faber textum Latinum et annotationes suas simul editas, alia et alia versuum distributione coagmentarat :—tum vero Stephanus, Fabri, opinor, invento aliquid addens—” {Latin: “And before that Jacobus Faber put together a Latin text with his notes printed with it, variously divided into verses:—and then Stephanus made some additions, as I see it, to the invention of Faber.”} And I have before me Sanctes Pagninus’s Bible, 1528, with Tmematia, as Henry would call them, marked by numerals in the margin, and the text divided by a lunula ⁌. Henry Etienne says, that his father was inventor of our division of verses, and that he himself was collator of MSS. for his father’s second and his third edition. [Specimen 13] The learned say, that his father was first inventor of such a division, and that Henry was sole collator.

P. 56. “To which add Beza’s testimony to the same purpose. Ad haec omnia accessit exemplar ex Stephani nostri bibliotheca cum viginti quinque plus minus manuscriptis codicibus et omnibus pene impressis diligentissime collatum.” {Latin: “In addition to all these there is an exemplar from the library of our Stephanus, a very diligent collation of twenty-five, more or less, book-form manuscripts and almost all the printed texts.”}

Here Mr. P. tells us, and upon the authority of Beza himself, the person who had the book of collations, and who, if we except the man from whom he received it, is now the only possible authority, that there were XXV ± MSS.; XVI of which, as we learn from Stephanus’s preface to his folio, were collated three several times; and almost all the printed editions. Now to suppose that the whole business of collation was performed by one single man, appears to me so gross, that I think no one who had fairly stated what the work really was, could have maintained the notion for a moment. I say, therefore, without any further evidence than this, not only that there exists not the least proof that Henry did the whole; but that it is a perfect absurdity to have ever imagined it. His age (18) at the time of the first collation, four years before the N.T. was published “grandibus characteribus et magno volumine,” {Latin: “in larger typeface and a large-sized volume”} says loudly with respect to that, “not Henry.”

P. 56. “Thus Beza in his first edition of 1556. But in his second edition, when R. Stephens was dead, these important words follow after impressis {Latin: “printed texts”}: AB HENRICO STEPHANO EJUS FILIO ET PATERNE SEDULITATIS HEREDE quam diligentissime collatum.” {Latin: “a very diligent collation PERFORMED BY HENRY STEPHANUS HIS SON AND HEIR TO THE CAREFUL WORK OF HIS FATHER.”}

And what were “the important words,” “when R. Stephens was” alive? “Sed quod ad vetera N. T. Graeci exemplaria attinet, quorum fides et authoritas in his annotationibus saepissime citatur —— de hoc te commonefaciendum per me putavit illorum author——” {Latin: “But what relates to the ancient exemplars of the N. T., whose trustworthiness and authority is frequently referred to in the these notes——on this matter you should treat them as I do as the conjectures of their author.”} Thus, at the end of the Apocalypse, “Lectorem monuit typographus {Latin: “the printer advised the reader”}, Edit. 1. f. 335,” as Wetsten says, 148. 7. (381 Semler): so Mr. Porson must have [Specimen 14] been well acquainted with “these important words:” for after all his ridicule of the poor Archdeacon, we cannot suppose him to have been ignorant of Wetsten’s Prolegomena; where we find them so distinctly cited. Indeed he refers to them himself; Gentleman’s Magazine, 1790, p. 128b. Kidd, p. 353. Travis himself, after Mr. P. had forced him to read it, gives the words at p. 247, 3d edit. This was the best possible method of authenticating the various readings which Beza gave from the XXV ± MSS. “(cum alia tum ea omnia que in regis Gallorum bibliotheca extant, {Latin: “when all those other ones were also then present in the library of the king of France”})” not merely the eight that were collated with the text of the folio, but the XV,—ea omnia {Latin: “all those”}, that Stephanus had received from the King’s library; as we learn, from his Resp. ad Cens. Theol. Paris. p. 37. given by Wetsten in loc. p. 724; in the French, leaf 23. But in Beza’s “second edition, when R. Stephens was dead,” it is pretty evident that this could not stand: the paterna sedulitas {Latin: “careful work of his father”} could not then be vouched. So in criticism, as in law, you must be satisfied with the best evidence that does exist. This was he, who bore so large a part in the two latter collations for the two editions, 1549, 1550; when he became a man, and was capable of it. The paternae sedulitatis haeres {Latin: “heir to the careful work of his father”} is therefore now appealed to, and “these important words follow after impressis AB HENRICO {Latin: “printed BY HENRY”}” &c. Suffer me then to take the important words of both editions—and I cannot conceive how Beza’s work could exhibit more decisive evidence of the truth of those various readings which he gives from all parts of the exemplar—readings selected from the whole of the XXV ± MSS. that Mr. Porson so justly tells us, had been collated.

P. 56. “Observe in all this proceeding the craft of a printer and editor.”

I say, “Observe in all this proceeding the craft of a” critic, who finds it necessary to get rid of the labors of the poor “printer and editor.” Let us see how, that which should have been for their health, is to be unto them an occasion of falling. [Specimen 15]

P, 57. “Robert was aware that by telling his readers who was the collator, he might infuse a suspicion into their minds, that the work was negligently performed: he therefore carefully avoided mentioning that circumstance.”

The first piece of craft, is such as that which is here charged upon Stephanus, the suppression of truth. Richard “was aware that by telling his readers who was” the printer of Beza’s 2nd edition, he must banish all “suspicion” from “their minds;” “he therefore carefully avoided mentioning” the circumstance, that Henry printed the second edition of 1565, as Robert did the first of 1556. So that each afforded the best possible evidence, then in existence, for the accuracy of the “exemplar cum viginti quinque plus minus manuscriptis codicibus diligentissime collatum.” {Latin: “a very diligent collation of twenty-five, more or less, book-form manuscripts and almost all the printed texts.”}

Craft the second is more audacious: we are told that “Robert was aware”—that Robert “therefore carefully avoided.” Did Robert then write the preface? Did he write one word of the book, except what we have seen above? I thought that it was “Beza’s testimony,” and that it was “Thus Beza” spoke “in his first edition of 1556.” But Richard “was aware” that if he had made it to be Beza, that carefully avoided mentioning the circumstance “in his first edition of 1556;” the question: would recur, what made him to be so careful to publish it in his edition of 1565? As Beza’s various readings were taken from the different collations of the XXV ± MSS. of Stephanus, he most certainly would carefully avoid mentioning any circumstance, that could derogate from their authority. So far the story goes very well: but we were promised to have craft shewn us “in all this proceeding.” How comes it then to turn to driveling imbecility; and that the secret, upon the keeping of which every thing was to depend, should be blabbed in the edition of 1565? And what was the death of Robert to do with letting out the circumstance, which they were so carefully to avoid mentioning, according to Mr. Porson’s [Specimen 16] theory? Is Beza to have common sense only on the tenure of Robert’s life?

A third piece of craft is seen in the “suspicion” which Mr. Porson takes care to infuse into the minds of his readers, “that the work was negligently performed” in all its parts. Wetsten’s quotations, as I have acknowledged, give us nothing that can affect the first edition; but they refer to the second and the folio, when Henry came to have any part of the work—“primo quidem minutioribus typis—mox autem grandibus characteribus;” {first in smaller typeface, but soon in larger”} and they prove sufficiently the attention that was bestowed on that part of these collations, be it what it would that fell to his share. And other testimonies may be found: I have observed one myself in the Thesaurus, Vol. I. p. 253 b, on αιτιαμα {Greek: “request”}. I am aware that these do nothing for settling the authority of 1 John v. 7, 8. which was fixed before Henry could have had any share in the work. But, let it be remembered, that the XVI MSS. from which the new text for our passage was formed in the first edition, were submitted, as well as the others, to the critical eye of Henry, who has evinced all this accuracy, and that the new form was continued, with a correction of its typographical error in the second, and afterwards in the folio.

A fourth piece of craft consists in the calm assumption, that there could be but one person to perform the work of all those different collations. The writer of the preface, call him Robert or Theodore, as you like, “carefully avoided mentioning the circumstance” that Henry was the sole collator, for the best of all possible reasons, namely, that he was not the sole collator. “By telling his readers” that Henry “was the collator,” he would not have been infusing a suspicion into their minds, that the work was negligently performed; but he would have been infusing a direct falsehood. Mr. Porson was aware of this, when he came to reprint this letter. It is recorded in Stephanus’s preface to his folio, that the second authority of those whose various readings are given in the margin, was collated by some friends in Italy. If Henry’s mode of expression could mislead any one [Specimen 17] in the quotation from his preface to Marlorat, as we see it has done in that from his Concordance; here was a decided fact, that left no room for doubt. Did this then make the Professor retract the hasty absurd deduction, that no one but Henry had any share in all the work of collation? Mr. Porson, it is true, declared that he was always unwilling to attribute to fraud, what he could with any reasonable pretence attribute to error. But this, let it be observed, was error to be ascribed to Stephanus; not one of such importance to be acknowledged for himself. Rather than avow this one error of his own, he attributes, without any pretence whatever, two frauds to Stephanus. It is thus that Mr. Porson gets rid of Stephanus’s flat contradiction. He now adds a note,

P. 57, note. “With the same caution, speaking of his No. 2. (now our Cambridge MS.) he calls it exemplar vetustissimum in Italia AB AMICIS collatum {Latin: “a very ancient exemplar collated BY FRIENDS, αντιβληθεν {Greek: “used for opposing readings”}. Without fairly confessing or openly violating the truth, that it was collated by his son Henry, he disguises the fact in a general expression. I have not forgotten Mr. Travis’s masterly construction of the sentence, p. 284, ‘It was the exemplar, the book itself, then (and not the lections out of it) which was collected or (rather) procured for R. Stephens, by his friends in Italy.’”

If Mr. Porson had said that No. 2. as far as we know of it, and our Cambridge MS. are the same for all critical purposes, no one would controvert it. But when such a man asserts, that they are one and the same, it ought to be observed, that he is only repeating Wetsten’s blunder; which was corrected by Semler, note 44, who refers to Simon (sur MSS. p. 60.) “et caeteri omnes eruditi {Latin: “and all the other learned”}.”

Mr. Porson notices the Archdeacon’s mode of construing Stephanus; and his own is scarcely less to be admired. As Trinculo says in the play, “misery acquaints a man with strange bed-fellows.” Neither of them chooses to let the Italian friends have any concern in the collation. As Henry says, “opera mea collatum, {Latin “collated by my endeavors”},” Mr. Porson will not allow it possible that one morsel [Specimen 18] of the work of collation could be performed by any one else. As Beza says, on 1 Cor. vii. 29, “Sic lego et distinguo hunc locum ex sedecim vetustorum Stephani codicum {Latin: “Thus I read and make out this place in the text from the sixteen very ancient book-form manuscripts of Stephanus”},” Mr. Travis, who can think of nothing but the marked copies of Stephanus’ margin of his folio, is pleased to conclude, ed. 3, p. 397, note, “that R. Stephens had in his possession the MS. β;” which, by the bye, had not the epistles.

In Italia ab amicis collatum {Latin: “in Italy collated by friends”}, says Stephanus. “This sentence (as Mr. P. says on another clause of this preface, at p. 63,) to an ordinary reader, would be very intelligible, but Mr. Travis is no ordinary reader.” No: nor yet was either of his correspondents.

“Collatum {Latin “collated”} αντιβληθεν {Greek: “used for opposing readings”} of Stephanus must import” says Mr. Travis (284, 2d edition, and he has the hardihood to repeat it, 397, 3d edition) “that the exemplar, the book itself was procured (and not the lections out of it collected) for R. Stephens, by his friends in Italy.”

Ab amicis {Latin: “by friends”}, “by his son Henry,” says Mr. P. “he disguises the fact in a general expression.”

“In Italia” Mr. P. does not meddle with; but if β is to form one of the “sixteen copies in the gross,” as Mr. P. calls that set of MSS. from which the first edition was formed, (p. 63,) and it was collated for that edition by Henry in 1546; then “in Italia” by an easy substitution of Cis-Alpine Gaul for Trans-Alpine, must be construed “at Paris:” because Henry never went to Italy till 1547.

According to Mr. P. what Stephanus says is “craft”—“caution” —“without fairly confessing or openly violating the truth.” The latter is much more than I can say of Stephanus’s commentators. Show me, if you can, the slightest ground for suspicion, that the words of Stephanus were not perfectly true, in their plain and obvious sense—except that it flatly contradicts the assumption, that there was but one set of MSS. but one collation of that set, and but one person to make that collation.

And if Stephanus found it necessary carefully to avoid men- [Specimen 19] tioning who was the collator of β—if “prudential motives induced him at that time to conceal his name,” (note 113, p. 690, on Michaelis, vol. ii. p. 238,) I should like to know why he could not hold his tongue here, as you are pleased to say he did in Beza’s preface. I ask Mr. Porson’s dupes, for what possible reason Stephanus should make any distinction with respect to β; but that it was actually collated by different persons, and in a different place from the other XIV. of the margin. Was the worrying of Erasmus, and the jealous watching of the Paris divines, to induce Stephanus to make this seeming mistake on purpose; furnishing such inquisitive readers, as Mr. Travis and his two correspondents, with the means of detection?

P. 57. “Another instance of this management may be seen in the preface to his first edition, where he says, that he has not suffered a letter to be printed but what the greater part of the better MSS. like so many witnesses, unanimously approved.”

The self-same management, if management it is to be, attended the conclusion, as well as the commencement of his critical labors. In his Respons. p. 36, he gives us his firm reply to Castellan, who had reprobrated his obstinacy, in not giving way to the tampering of the Sarbonne. “Nego me posse adduci ut unquam contra fidem omnium codicum quicquam mutarem, atque ita falsarius deprehenderer.” {Latin: “I deny I could be adduced to change anything whatsoever contrary to what is reliably assured by all the book-form manuscripts, and so be caught doing something fraudulent.”} French, leaf 22, “Je luy di que jamais on ne m’eust sceu amenera a ce point, de changer rien au texte contre ce qui se trouuoit par tous les exemplaires pour estre par ce moyen trouue faulsaire,” {French: same as Latin.} (Maittaire, p. 67.)

P. 57. “‘ This boast is indeed utterly false, as all critics agree, who have taken any pains in comparing Stephens’s editions,”

I know that all critics do agree in this—all who have taken pains to produce new editions, and those who have enlisted under their banners. I am perfectly aware of the conspiracy, and of the causes of it. I am aware, too, that the ipse dixit {Latin: “personal viewpoint”} of these critics, who do thus agree, passes as irrefragable, with a [Specimen 20] world which is much more ready to take upon trust, than to take the pains of examining. These critics, however, we are told, have taken pains in comparing Stephens’s editions. Comparing them with what? With the MSS. from which Stephanus professed to form them? No. I know that Mill has sapiently collated the first edition with another set; and whoever considers the result of that collation, will see that this must have been the case. But when they make their modest assertion, that Stephanus’s boast, with respect to his first edition is “utterly false,” Task, what do they know of the XVI MSS. from which he thus solemnly protested, that he never deviated? I quote the words of “that Divine,” who, as Dr. Carpenter says, (ag. Magee, p. xxxiv.) “holds the first rank among our English critics,” when I tell you of MSS. being “at present either lost or buried in obscurity, in the same manner as the Codex Boreeli, the Codex Camerarii, the Codex Rhodiensis, Erasmus’s MS. of the Revelation, and several other manuscripts of the Greek Testament, used by Stephens himself”—Note 114, on Michaelis II. P. 239, p. 698. If I allow that VIII. out of the XV. MSS. which he had from the King’s library (Respons. p. 37, as above) were those identical royal MSS. whose various readings are given in the margin of the folio; who, I pray you, has collated the remaining VIII of the first edition; who can pretend to tell me what they are, and in what state they are? And who, I ask you, can tell me any thing of the MSS. used for forming the text of the folio; but from those various readings that are given in the margin? for I think that those preserved by Beza will not enable you to fix upon the rest. Mr. Porson says, p. 232, “Who ever called R. Stephens a cheat, because he retains many readings in his edition which he found in no MS.?” I am afraid that I shall not be equally polite to the gentlemen who make the assertion, that R. Stephens retains many readings in his editions which he found in no MS. But it should seem that, according to Mr. P. Stephanus’s guilt is to be proved by comparing the editions with one another. [Specimen 21]

P. 58. “They know that Stephens has not observed this rule constantly, because his editions often vary from one another,——”

Does it then follow that the editions cannot each be taken from MSS. because they vary from each other? Griesbach’s editions vary from each other, but I never heard this inference drawn with respect to them. The variation, I have understood, might be accounted for, so as to leave Griesbach in possession of his “boast.” Old MSS. might have been better collated, or new ones might have been obtained; and thus the 2d edition might give new readings. I have yet to learn why this might not be the case with Stephanus. I am here directly at issue with the conspiring critics, who it seems are not “always unwilling to attribute to fraud, what they can” very reasonably attribute to the man’s doing his duty as editor. “His editions often vary from one another.” Well; this is one reason with me for believing that he followed his MSS. I do not infer what they, technically I presume, call “management.” My inference is, that the materials from whence the editions were formed, had varied. It will be for the reader to decide, whether Stephanus’s boast and my logic be “utterly false, as all critics agree:” and it may be of some use to him in making his decision, to observe that the XVI original MSS. were, as Stephanus declares in the preface to the folio, collated three times over; and that, as Mr. P. himself has just informed us, they were increased in number to XXV±; or as the man who must know best—he who superintended the work for the second and the third edition has stated it, to more than thirty. (Praef. to ed. 1587, in Wetsten, p. 143. Semler 369.)

P. 58. “——and in his third edition often from all his MSS. even by his own confession.”

This is a curious confession for any editor to make: and, let it be observed, Mr. Porson himself has told us the moment before, that Stephanus, when he published his first edition, declared [Specimen 22] that he had given nothing “but what the greater part of the better MSS. approved;” and, as we have just seen, “this boast” was pretty nearly repeated, after he had concluded his third edition. It is also a curious circumstance, that this confession was utterly unknown for fourscore years; during which time it was universally believed that he had always followed some of the XXX+ MSS. that his son Henry said he had seen; though the good doctors of the Sarbonne were as anxious to demolish his N. T. as Wetsten, Griesbach, or Mr. P. could possibly be. But Mr. Porson tells us, that the critics know that he actually did make such a confession. Why then, when they have Stephanus confitentem reum {Latin: “confessing that was so”}, I think we might expect to be shamed by the words of the confession being blazoned before us; or, at least, some reference to the place where it was registered. I want to know under what circumstances he was brought to this most wonderful confession; and who were the witnesses. I must add also, that I should like to have the very words in which he acknowledged his guilt. I am fresh from that admirable piece of criticism that makes “in Italia ab amicis,” to mean “my son Henry at Paris;” I should like therefore to be allowed to see myself that the words attributed to him actually express that his text varies from all his MSS.

P, 58. “But because Mr. Griesbach took this point for granted; not foreseeing that a man would be found so hardy or ignorant as to deny it, you insult him, p. 298, and call his assertion groundless, improbable, uncandid, and injurious, These are the magic words that have charmed your converts of the first eminence.”

Mr. Griesbach, in the whole of his most able and judicious work, never showed, according to my notions, so much judgment, as he did, when he “took this point for granted.” But when the professed defender of Stephanus came to it, did he not exult? was there no song of triumph? No. Mr. Travis had nothing but those “empty visions,” in his poor “brain.” Nothing could satisfy him, but grex noster {Latin: “our herd”}: he must have the authority of [Specimen 23] every MS. in the margin of the folio. One out of the “XXX et plures,” {Latin: “30 and more”} seen by Henry, was nothing to a man, determined to have a majority of all known MSS. for the heavenly witnesses; so the text copied from the little editions is utterly beneath his notice. “Give me” XVI. “or else I die.” The reader will see that there is great danger of my insulting Mr. Griesbach, much more than the poor Archdeacon did: groundless, improbable, uncandid, &c. would certainly not satisfy my notions, They appear to me as vapid as the Archdeacon’s accusation. When these editions of Stephanus have the inestimable value of having been begun with a determination of quitting the received text, (of Erasmus) wherever it was not supported by the XVI MSS, with which these editions commenced—and of having approached nearer and nearer to it, as the collation became more accurate, and the number of MSS. increased; I cannot stand unmoved, at seeing a modern editor at once throw them aside; taking it for granted, that Stephanus often varied from all his MSS; or at least allowing them to have then only any value when the received text opposes them.

And now, when the fact of the point having been thus assumed, is fairly acknowledged; what is the case with him whose talents, even among the Wetstens and the Griesbachs, shine forth, “velut inter ignes luna minores?” {Latin: “as the moon among the lesser lights.”} Mr. Porson too “took this point for granted.” And yet, to adopt Mr. P.’s words at p. 60, “up starts a grave and reverend gentleman, and tells us with a serious face,” that Professor Porson “has left nothing to be said on the subject [of the disputed passage] either in vindication or reply.” (Dr. Adam Clarke, end of his note.) Here is an accusation, which involves not merely our passage, but the whole N. T. Did Dr. Clarke pass this over, as unworthy of his notice; or did he really think, that the Professor left nothing further to be said, when he “took this point for granted?” And did Dr. Adam Clarke think himself warranted by this assumption, to say (Sacred Literature, p. 85,) that “of all the MSS. yet discovered, which contain this epistle, amount- [Specimen 24] ing to more than one hundred, only three, two of which are of no authority, have the words.” It is true that we have in Mr. Porson, “the magic words,” hardy or ignorant “to charm his converts of the first eminence.” But even after the Professor’s anathema, there is a man to be found, “so hardy or ignorant as to deny it.” Ecce adsum qui feci {Latin: “Lo it is who did it”}; ignorant of any place where Stephanus has told us any thing about the reading of “all his MSS,” except that of 1 Cor. xv. 51. to Castellan, in his Resp. p. 36, referred to above; hardy, because Mr. Griesbach is thus “deserted at his utmost need.” I cannot help suspecting that Mr. Porson was aware, either that the document, upon which they depend, was a forgery; or that the confession did not amount to varying from all his MSS.

P. 58. “Editors and printers are such conscientious people, that we may be sure they will never practise any tricks of their profession, or give their own publications undeserved praise.”

I beg the reader to observe, that I make no such claim for those contemned beings, that have been “editors and printers.” But I do demand for them, that they shall not be assumed to be guilty, without proof: and I shall not suffer myself to be duped by the editors and critics, when they practise the tricks of their profession; and would establish their editions, on the ruin of all their predecessors, by taking this point for granted.

P. 58. “And whoever offers to think that they may sometimes bestow extravagant commendations on their own labour, diligence, or fidelity, is totally void of literary candour and Christian charity.” (p. 59. 125.)

When the editor and printer in question, gave such solemn assurances, both at the commencement, and after the conclusion of his labors; and these assurances were never called into doubt, for eighty years, by his bitterest enemies; “whoever offers to think” that he violated these engagements, merely on the ground that those, who would find him a troublesome evidence, have [Specimen 25] “agreed” to take “this point for granted,” I should search out for some more appropriate “terms, to give him out,” than those which denote want of literary candour, &c. whether it be the head, or the heart, that is in fault.

P. 58. “But an example will make this position clearer.”

It seems that Mr. Porson after all, thinks that he can find one instance. It is enough to say, in the words of the adage, that one swallow does not make summer. Still a single instance would throw some suspicion; let us therefore see the utmost that the Professor can do.

P. 58. “In the eleventh verse of the second chapter of Matthew, all the MSS. the Complutensian edition, nay the very MS. from which Erasmus published his edition, have ειδον {Greek: “they saw”} instead of ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”}, but Erasmus upon the single authority of a faulty copy of Theophylact, altered it to ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”}; Stephens in his third edition followed Erasmus, and ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”} infects our printed Testaments to this day.”

“Stephens in his third edition.” What is the third edition to me, more than any of the Elzivirs? I thought that we were to have an example that would make Mr. P.’s position clear, with regard to that which alone concerns the question about 1 John v. 7,8. No. Mr. Porson will not “be found so hardy, or so ignorant,” as to tread in the steps of Mill, 1177, &c.; and to pretend to pick out one single instance, in the edition which gave our passage in the new form—that form, which “infects our printed Testaments to this day.” But a single instance, even from the third edition, might reflect back some shade of suspicion on the first, and give some room for a possibility of doubt respecting our text. Let us follow Mr. Porson then.

“All the MSS.” All what MSS.? If this means all the MSS. that Mr. Porson ever saw, I shall readily allow it: and shall, like our learned translators, and their predecessors in [Specimen 26] the Bishops’ bible, bow to the sentence which he pronounces, that ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”} infects our printed Testaments; though Whitby and Wolfius were of a different opinion. But this is not enough; it is not sufficient for him to show, that almost all the MSS. of Griesbach (Codices tantum non omnes {Latin: “only not all the book-form manuscripts”}) have ειδον {Greek: “they saw”}, he has to prove that not one of Stephanus’s had ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”}: and when it comes to the point, you see that Mr. Porson will not undertake this.

Stephens in his third edition followed Erasmus. Very well: and what then? I have no doubt that he made it the general principle of his third edition, to follow Erasmus’s text, (the then received text,) wherever he found it supported by his own MSS. His first edition then has “ειδον {Greek: “they saw”} instead of ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”};” and I am ready to allow that, when he “altered it to ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”},” in his third edition; he “followed Erasmus.” Was it impossible for him to copy a Greek MS. (it shall be as bad as you like,) when he thus followed Erasmus? Mr. Porson takes this point for granted. Now mark how much better Wetsten does this: “Erasmus in codicem vitiosum Theophylacti incidens, qui pro ειδον habebat ἑυρον, codicem 2. quem typographis edendum dedit, sua manu correxit, cui Stephanus editione tertia, reclamantibus, ut fatetur, omnibus suis Codicibus temere adstipulari non dubitavit.” {Latin: “Erasmus came across a faulty book-form manuscript of Theophylact which had ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”} instead of ειδον {Greek: “they saw”}, book-form manuscript 2., which he arranged to be printed in an emended form, corrected by his own hand, and which Stephanus in his third edition, rejecting, as it is said, all his Book-form manuscripts, doubted not to have the temerity to uphold.”}

This is like a man: you have the proof positive, you see, from Stephanus’s own confession: and it is not “all the MSS.,” but “omnibus suis codicibus,” {Latin: “all his book-form manuscripts”} which is repeated upon our passage, p. 724, 2nd par.—ipsa Stephani editio palam testatur, editorem a lectione omnium suorum codicum recessisse, et aliam lectionem recepisse—.” {Latin: “the edition of Stephanus itself plainly bears witness that the editor rejected the testimony of all his book-form manuscripts, and accepted another reading.”} With this, what wonder that the Archdeacon of blessed memory, should add in his third edition, p. 188, this note (k) to what he had given in his 2nd ed. p. 118. “In Matthew ii. 11. R. Stephens follows Erasmus in writing ἑυρον instead of ειδον: they FOUND, instead of they saw the child. And this circumstance has been amplified into a desertion of his plan, as well as of his MSS. But the charge is ill-founded. His plan was to accept, by whatever hand it might be offered, that [Specimen 27] which appeared to him to be the genuine reading of Scripture. And he accorded with Erasmus in preferring ἑυρον, {Greek: “they found”} probably because (both words affording nearly the same sense,) the same verb, ἑυρητε, {Greek: “you found”} occurs before in the eighth verse. In acting thus, therefore, he deserted not his plan, but followed it. Nor did he, in any culpable sense desert his MSS: for he tells us frankly, ειδον εν πασι, All my MSS. read ειδον {Greek: “they saw”}.” Dr. Hales too, Faith in the Holy Trinity, (1818.) vol. ii. p. 19. “Griesbach objects, that “Stephens frequently follows Erasmus, contrary to the credit and authority of all his MSS.” Proleg. p. xviii. This censure is praise.—Stephens did not, like Griesbach, servilely follow the external evidence of manuscripts, versions, and fathers only; he carefully weighed the internal also, and made that his chief standard. Of this we have a remarkable instance in Matt. ii. 11. where he follows Erasmus in the reading ἑυρον, “they found,” instead of ειδον, “they saw.” Though he candidly confesses, ειδον— ―εν πασι, “All my MSS. read ειδον ” {Greek: “they saw”}. ― “He, therefore, was fully justified in rejecting the authority of all his Greek MSS. upon such a combination of evidence.” p. 20. It may appear very invidious in me, to take upon me to decline, for Stephanus, all this praise, which Dr. Hales finds in Griesbach’s censure. But the truth must be told. Stephanus, poor simple man, did not think himself “fully justified in rejecting the authority of all his Greek MSS.” And to talk of his “deserting his MSS.,” and not doing it, “in any culpable sense,” he would have said, was nonsense. The whole praise that he claimed, was that of making a selection from his MSS., and giving a text accordingly. “All critics agree,” as Mr. Porson tells us, to deny this to him; but they shall see, and be ashamed for their envy. (Isa. xxvi. 11.)

As, however, Erasmus is introduced, to make out that no MS. authority existed; a word or two must be premised respecting him. “Erasmus upon the single authority of a faulty copy of Theophylact.”—There happens to be another “single authority” (more last words of Mr. Baxter,) Wetsten Prol. 44. [Specimen 28] (116 Seml.) on this very codex 2, “quem typographis edendum dedit,” {Latin: “which he arranged to be printed in an emended form”} speaking of the corrections by Erasmus, has—“Matt. ii. 11. ειδον {Greek: “they saw”}] ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”} ex Versione Vulgata {Latin: “from the Vulgate Version”}:” and let it be observed, this is not an old forgotten piece of criticism, reprinted from the edition of 1730: for it does not appear there, see p. 58. Mill in Loc. was able to find another “unum excipiam Epiphanium et Vulg. Interp. {Latin: “I except uniquely Epiphanius and the Vulgate Interpretation”}. “Whitby Exam.—yet another “Hieronymus vero Vulg. Epiphanius {Latin: “Jerome, the Vulgate and Epiphanius”} ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”}.” Now I should like to know how Wetsten and our Professor would have accounted for the existence of all these proofs of the faulty reading: and till I am informed, I shall take the liberty to suppose that they came from some faulty Greek copies, one of which furnished Erasmus with his correction. If Mr. P. had been able to keep, for five pages, to his principle, “I am always unwilling to attribute to fraud what I can, with any reasonable pretence, attribute to error,” he would still have not stood singular in taking such a solution; for Mill says, 1229, “ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”} quod reperit in uno fortasse aliquo Cod. Erasmus obstinate retinuit {Latin: “which Erasmus found perhaps in some one book-form manuscript or other and obstinately retained”}; which I think is not absolutely contradicted by Griesbach’s “Codd. tantum non omnes {Latin: “only not all the book-form manuscripts”}.” Wetsten laid down his charge of villainy against Erasmus in good round terms, in the first edition of his Prolegomena, 57 bott. (ante tamen Erasmus hunc codicem ad fidem Theophylacti aliorumque Patrum, interdum etiam ex conjectura correxit {Latin: “However before this Erasmus corrected this book-form manuscript on the basis of Theophylact and other Fathers, also in the meanwhile from conjecture”}); but he found himself obliged afterwards to correct his own conjecture; and had to add, after “aliorumque Patrum {Latin: “of other Fathers”},” et ex Versione Latina, aut aliis codicibus Graecis {Latin: “and from the Latin Version or other Greek book-form manuscripts”}, Prol. 44. Seml. 116.

Now, then, for those who charge Stephanus with avowing that he gave his text contrary to all his MSS., and those who glory in the charge. I say, in the name of common honesty to the one party, and in the name of common sense to the other,— where has he confessed that he has given the reading, “reclamantibus omnibus suis MSS. {Latin: “rejecting all his Book-form manuscripts”};” where does “ipsa Stephani editio palam testatur editorem a lectione omnium suorum codicum recessisse {Latin: “the edition of Stephanus itself plainly bears witness that the editor rejected the testimony of all his book-form manuscripts, and accepted another reading.”}?” Where does he tell us frankly—where does he candidly confess, “All my MSS. read ειδον {Greek: “they saw”}?” Where, ex- [Specimen 29] cept as before excepted, to Castellan, does he himself say any thing about the reading of “all his MSS.?” Where does he say a word of the reading of any, but the XV of the margin, except in the case referred to above; viz. Eph. iii. 1., where, as Griesbach’s says, “κεκαυχημαι” {Greek: “I have boasted”} alii apud Stephanum {Latin: “Other witnesses in Stephanus”}?”

I can very readily believe that when the good Archdeacon and his disciple of Killesandra inserted the possessive pronoun, and made ειδον—εν πασι {Greek: “they saw—in all”} to express “all my MSS. read ειδον {Greek: “they saw”},” they very honestly believed that all the XV of the margin had this passage, and gave ειδον {Greek: “they saw”} instead of ἑυρον {Greek: “they found”}. Poor Travis says for Stephanus, with respect to 1 John v. 7, 8. “In all my Greek MSS. from whence I compiled my Greek edition of A.D. 1550, the whole of the same disputed passage is also read, except in seven only—” 2d ed. 302, 3d ed. 415. I should not, however, be charitable enough to think so of the man, who inserted “suis,” and said, “reclamantibus, ut fatetur, omnibus suis codicibus” {Latin: “rejecting, as is claimed, all his Book-form manuscripts”}. I should say that Mr. Porson, whose judgement is no less to be admired than his acuteness, had reason sufficient for not committing himself to Wetsten’s assertions on Matt. ii. 11, if he saw only in what a different manner he could express himself respecting the reading of αδελφους {Greek: “brothers”}, Matt. v. 47, which stands in precisely the same circumstances. “Erasmus tamen, qui testatur plerosque Graecos codices habere φιλους, et Stephanus qui φιλους εν πασι reperit, hanc lectionem nescio qua de causa secuti non sunt.” {Erasmus however who testifies that the majority of the Greek book-form manuscripts have φιλους {Greek: “friends”}, and Stephanus who found φιλους εν πασι, {Greek: “friends in all”} I know not why they did not follow this reading.”} I should go on to say, that Wetsten might have been able to see it possible for Stephanus, “who found φιλους εν πασι, {Greek: “friends in all”}” still to maintain his boast of never giving a reading that was not supported by his MSS., whilst he retained αδελφους {Greek: “brothers”}. I should even say, that he was well aware that Stephanus never confessed that he had in all more than ten of his MSS. against him. I should say this, if I had seen only his boast, p. 146. 3. (Seml. 375.) that he had supplied Stephanus’s omission of giving a description of the MSS. of his margin, and “preter Complutensem Editionem habuisse exemplaria Evangeliorum decem, Actorum et Epistolarum octo, Apocalypseos vero non nisi duo.” {Latin: “Apart from the Complutensian edition, he had ten exemplars of the Gospels, eight of the Acts and Epistles, and no more than two of the Apocalypse.”} [Specimen 30] I am, fortunately, not left to draw the inference myself; and I thus escape the suspicion of being anxious to attribute to fraud, what I might have attributed to error, when I say that Wetsten, and whoever so far exceeded Mr. Travis in knowledge, as to have read through Wetsten’s Prolegomena (Porson 4. 56.74.) knew perfectly that the whole which could be said with truth was “reclamantibus, ut fatetur, decem ex iis Codicibus manu-. scriptis, quorum variantes lectiones posuit in interiori margine.” {Latin: “rejecting, as is claimed, ten of those manuscripts, whose variant readings he placed in the inner margin.”}

Wetsten has himself distinctly stated that εν πασι, in the gospels meant this, where he is giving his celebrated demonstration of the falsehood of the Barberini readings. P. 62. (162 Seml.) Bengelius had instanced John i. 42. “ubi differentia articuli Vulgatum non tangit, et Stephani margo plane vacat” {Latin: “where differences regarding the article does not affect the Vulgate, and the margin of Stephanus has nothing at all”}; he replies, that Caryophilus would argue “Stephani codices decem i.e, omnes legisse ὁ Χριστος cum articulo;” {Latin: “ten book-form manuscripts of Stephanus i.e. all of them read ὁ Χριστος, ‘the Christ,’ with the article”}; not you see here “omnes suos,” {Latin: “all his”} but “decem i. e. omnes;” {Latin: “ten, that is, all of them”} and he shows that no man of common sense and the least knowledge, could make any thing more of it, than that ten of the MSS. of the margin, two thirds only of that one set had the reading. When, therefore, Wetsten inserted SUIS {Latin: “his”}, to make Stephanus’s omnibus refer to it, “all his MSS.” instead of, all those of the margin that have the passage, was it, I ask, according to his Homeric prayer, that he professed, Prol. 205. (508 Seml.) ποιησον δ αιθρην, {Greek: “Clear the sky!” Iliad 17. 646}—or the Horatian, that he gives to his opponent, “Pulchra Laverna, Da mihi fallere?” {Latin: “Fair Laverna, grant me to escape detection” Horace, Epistle LXVI. 60f.} Who will now wonder that Mr. Porson should be himself, as we have seen he says of Stunica (p. 45.) “so mild and tame in this particular instance,” that when he comes to the point, he should make it “all the MSS.,” not all his, and should depend for his proof upon Stephanus’s text agreeing with that of Erasmus?

But Wetsten was driven to the ratio ultima {Latin: “ultimate argument”} of Critics. He had no other way of making out his point, viz. “in memoriam revocandum est, omnes vulgatas editiones non nisi ex duobus non optimae notae Codicibus, uno Erasmi, Complutensium altero, prodiisse” {Latin: “it must be recalled, all the common printed editions, not highly regarded, on the basis of only two Book-form manuscripts, one that of Erasmus, and the other the Complutensian, have given that reading”}; Animadvers. et Caut. II. p. 870, or as it stands in Bishop Marsh’s Lectures, VI. p. 110, “The text therefore in [Specimen 31] daily use resolves itself at last into the Complutensian and the Erasmian editions. Griesbach, p. V. (or XVIII. Lond. 1809): “Editiones omnes Elzevirianis anteriores, immo ipsa etiam Elzeviriana, e duabus recensionibus fluxerunt, Complutensium scilicet editorum et Erasmi.” {Latin: “All the editions prior to the Elzevirs’ originated from two recensions, that is, those of the Complutensian editors and that of Erasmus.”} This, Dr. Griesbach, in his excellent prolegomena, has placed beyond controversy.” Butler Hor. Biblic. I. p. 167. 4th ed. Had Wetsten ventured to say on Matt. ii. 11. reclamantibus codicibus decem, i. e. omnibus, {Latin: “rejecting ten of those manuscripts, i.e. all of them,”} I think there is no one, I do not except Archdeacon Travis, who would not have made some hesitation respecting the proof that Stephanus’s “third edition often varies from all his MSS. even by his own confession.” And this too, even supposing him to be in the most profound ignorance of Stephanus having spoken in his preface of another set of XVI. MSS.—of his having spoken in his answer to the Paris divines, of XV. from the royal library—of Beza’s testifying, as Mr. Porson has shewn us, that he had in all XXV±.—and Henry, the principal collator for the 2d and the 3d ed. having stated them at more than thirty. No creature could have allowed that “ipsa Stephani editio palam testatur, editorem a lectione omnium suorum codicum recessisse, et aliam lectionem recepisse:” {Latin: “the edition of Stephanus itself plainly bears witness that the editor rejected the testimony of all his book-form manuscripts, and accepted another reading:”} every one must have seen that “εν πασι {Greek: “in all”} in omnibus Codicibus” {Latin: “εν πασι, Greek: “in all,” in all the Book-form manuscripts”} never, in any instance, could possibly mean all, even of the one set, but merely all those of the XV. that happen to have the passage.